Hello, readers! Thanks for joining us, especially the newest people to check out CulinaryWoman. I hope you’ll enjoy the free version, and if you find it valuable, consider upgrading to a paid subscription.

We’re about to celebrate our second anniversary, and I will be rolling out new features available exclusively to members of the CulinaryWoman Community - our paid subscribers and generous founding members.

Community members already receive a heads up each week on what will be in the newsletter, and are eligible for giveaways ranging from my book, to cookbooks, yummy treats and beverages.

You can click this button to upgrade, and thank you very much indeed.

How A Family Heritage Inspired A Cookbook

Sooner or later, every food writer gets the same suggestion: you should write a cookbook.

I have not written one, and neither had Liz Williams, founder of the Southern Food and Beverage Museum and a leading culinary figure in New Orleans. She was already an author, and the idea of dealing with recipes simply did not appeal to her.

Then came a project to change her mind. Williams has just published Nana’s Creole Italian Table: Recipes and Stories from Sicilian New Orleans. It’s a compilation and memoir inspired by her grandmother, and it is loaded with tasty dishes brought here by the huge wave of 20th century immigrants.

Last week, Liz talked about her Sicilian roots in a city better known for its French heritage.

Visitors may not know that New Orleans gained a significant number of Sicilian immigrants in the late 1800s and early 1900s. The fruit companies who operated from the city’s vast docks were eager for workers. They set up offices in Palermo, offering direct passage to New Orleans from what was a rugged and impoverished island.

An estimated 300,000 people made the trek. Since the French Quarter was near the water front, the immigrants began settling there, soon overwhelming the available housing and prompting some established residents to move elsewhere in the city. The newcomers began to spread themselves into adjacent neighborhoods such as Treme. Now, it is a center of Black culture, but a century ago, Treme was home to Sicilians, including Liz’s family.

Dinner table discussions

Food was “very central” to her upbringing. “We talked about whatever we were eating,” Liz told an audience at a program sponsored by Gambit, the weekly magazine. “We talked about whether it had the right texture. We talked about whether there was enough garlic, was there enough balance between the sweet and the sour or whatever it needed to be. You were looking for balance - ‘oh, we should have put more wine in this,’ whatever. It was just part of the discussion at the table.”

As her family and other Sicilians began settling into New Orleans, they incorporated the ingredients and style of cooking known as Creole into their dishes. The term is credited to Lafcadio Hearn, a roving Greek-born newspaper and magazine writer who traveled to Britain, the U.S. and ultimately Japan in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. During his time in New Orleans, he popularized the image of the city that lingers to this day, publishing a Creole cookbook and a book of Creole proverbs. He wrote extensively about Mardi Gras, as well as New Orleans’s voodoo rituals.

To Liz, “Creole-ization is taking the food in New Orleans, whatever its influences, and allowing it to evolve.”

She tracks that “crystallization” in her book, which shows how recipes evolve. A good example is Creole tomato sauce, or what is known locally as “red gravy.” I learned to make it from Liz and the New Orleans writer Jyl Benson in a tutorial at SoFAB in 2017.

I grew up preparing my mother’s sauce, which begins by sweating - not frying - onions and garlic, for those who like it, and then building layers of flavor with canned and fresh tomatoes, plus herbs and other seasonings. It’s essentially a marinara, to which meat and more veggies can be added. Here’s what it looks like.

Red gravy looks like its name. It is a darker red, it is thick and the flavor is stronger. One reason is that it begins with a roux, rather than individual seasonings, and cooks down to get that denser consistency. Some recipes include chicken stock, which was never in my mother’s basic sauce. It could be finished in an hour or less. Here it is in progress.

“It was quicker, and it got thicker faster,” Liz says. Her grandmother only had one rule, though: “She would not put it on pasta. It was its own sauce.” (However, we had it on pasta at SoFAB that morning.)

Preserving cooking traditions

Listening to Liz’s evening worth of stories, it was natural to wonder why she had not written a cookbook before now (her duties founding and running the museum aside). “The reason is very simple. I hate to write recipes,” she says. “I'm one of those people who cooks by opening the refrigerator and seeing what's in there and just turning that into dinner.”

She has always viewed other cookbooks as “a suggestion” of what can be done with ingredients. The idea of duplicating a dish so that others can make it “requires a whole lot of discipline,” she says. “It may not be my last book, but my next is not going to be a cookbook.”

Even though the process was rigorous, I’m grateful to Liz for this combination of memoir and recipes. For anyone who wants to take a similar journey, Liz has a tip: cook with the oldest member of your family, and write down (or record) what they teach you.

“Do it while they’re alive, because when they are gone, it’s too late,” Liz says.

Taking care of my mother and Maxine into their final years, I found that even when they lost mobility, they were still able to instruct me. Maxine, whose peeling and chopping skills were as precise as a surgeon, was still acting as my sous chef until her last months.

“Even if you're just doing it for your family and not because you're trying to write a cookbook that you're gonna publish, I think that's really an important thing,” Liz says. “This is part of your family's heritage, and it's a way to share it with your children and your grandchildren.”

A Jewish Author Inspires A Jewish Baker

This week, I spent a delightful coffee hour with Nancy Pesses, who hails from suburban Metarie. I connected with Nancy earlier this spring, when she was one of the participants in Baking for Ukraine. Nancy joined bakers from all over the world in selling hamantashen, the traditional filled shortbread triangular cooking, and donating the proceeds to charity.

That was a sidelight to Nancy’s regular baking business, Challah Creations By Nancy. I love challah and promised to order some when I got to New Orleans. Every week, Nancy posts her flavors on Instagram and Facebook, and accepts orders for local pickup or for shipping nationwide.

This is great challah, and her variations are creative. I bought three loaves - cinnamon raisin, chocolate lover’s dream, and Mediterranean, which had olives, feta and tomatoes. My friends and I devoured it one evening and I’m already planning to get more.

People have urged Nancy to open her own bakery, but there’s a reason why she won’t: she is actually a veterinarian. She took up baking challah during the pandemic to soothe stressed nerves. However, she still takes care of small animals when she is needed by local pet owners.

I was tickled to learn that Nancy’s baking inspiration is Shannon Sarna, editor of The Nosher, and the author of Modern Jewish Baker.

Her upcoming cookbook, Modern Jewish Comfort Food, will be published in August. Shannon and I just participated in a Jewish Book Council authors’ event, and I’ll bring you more about her new book when it’s published.

A Chicago Fried Chicken Classic

Dozens of chefs are descending on Chicago this weekend to attend the James Beard Awards, which take place Monday night. The media awards were given out Saturday night. Congratulations to those winners, especially Dan Pashman and the team from the Sporkful.

My Instagram feed has filled up with friends’ reunions and dishes from restaurants across the city. Although fine dining might be in the spotlight, I hope some visitors will stop by one of the outlets of Harold’s Chicken Shack.

Harold’s might not be as famous as some of the country’s best known chicken spots, like Gus’s in Memphis (now a national chain), or Willie Mae’s or Dooky Chase’s in New Orleans.

But Harold’s has great significance to Chicagoans who love to eat, and particularly to members of the Black community. The first Harold’s was on South 47th Street, and Harold’s franchises became a way into business ownership for many people of color.

Everyone has a favorite Harold’s - mine is on South Michigan Avenue, and along with chicken, it featured slices of caramel and coconut cake, baked by local church ladies. My colleagues at WBEZ introduced me to Harold’s, including instructions to order mild sauce (if you know, you know).

You can read an extensive Harold’s history in this story from Eater Chicago.

Keeping Up With CulinaryWoman

I’ve been tickled to meet so many interesting culinary people here in New Orleans, and I’m happy to receive introductions. If you’re here or know someone here that I should meet, feel free to reach out. I am CulinaryWoman at gmail dot com.

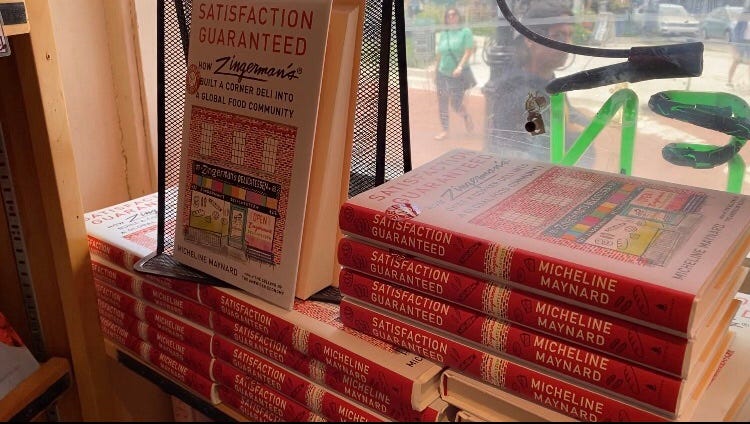

Thanks to everyone who has purchased my book, Satisfaction Guaranteed: How Zingerman’s Built A Corner Deli Into A Global Food Community. You can order from Bookshop.org, and I can send you a signed bookplate. Zingerman’s Deli has signed copies if you are in Ann Arbor, and Coutelier has some here in New Orleans.

Follow my Nola adventures @micki_in_nola on Instagram. I’m posting photos and Reels. You also can follow @culinarywoman on Twitter and Tik Tok.

Please stay well, and see you next week.

Next time I'm in NOLA, let's go to Dooky Chase's. Sounds great.